October 9, 2020

This week on SideBarre, lighting designer Jennifer Tipton steps into the spotlight.

"Behind every shining light on stage is a great lighting designer, but Jennifer Tipton doesn’t exist in the shadows. She is a giant in her industry."

Light. For the most part, we just accept it. We don’t question it nor may we even think about it. We take for granted that we are able to see, and that light will continue to allow us to see. There is a reason why darkness can evoke so much fear—light illuminates our world into abundance. Without its presence, so many things just disappear.

There is a certain place that one takes note of the light. In the theater, when the lights dim to signal the start of a show, it brings a collective hush over an eager audience and the late comers scrambling to find their seats.

With the darkness comes a flood of anticipation. We gladly accept ourselves disappearing into the blackness, for the light that appears before us creates another world to immerse ourselves within. It is so seamless that we do not even notice the light that took us there.

Behind every shining light on stage is a great lighting designer, but Jennifer Tipton doesn’t exist in the shadows. She is a giant in her industry, a revered and respected artist who has won too many awards to count: a MacArthur Grant, a Laurence Olivier Award, two Bessies, two Tonys®, two American Theatre Wing Awards to name a few. Jennifer’s work, both in theater and in dance, is known and beloved around the world.

Now a Professor of Design at the Yale School of Drama, Jennifer’s roots began in modern dance. The summer between her junior and senior year of high school in Columbus, Ohio, Jennifer went to the American Dance Festival, where she fell in love with the Graham technique, created by American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham.

She loved it so much that during her senior year, she spent two weeks in New York by herself, studying at the Martha Graham Dance Company studios. Although she transitioned into lighting design after graduating from Cornell University, her dancer’s eye has always remained sharp, intuitive and essential to her lighting.

So how does lighting design work? When working on a new ballet, Jennifer would go see the work in the studio and was often one of the first people to see the whole ballet with virgin eyes. Arriving simply as a viewer, she would ask the choreographer not to talk to her about the piece until she had seen it. “If the choreographer tells me certain things, like [the dancers are] reacting to a ghost at this point, then I will see the ghost” she said. Her independent notions that she then formed about the ballet allowed her to aid the choreographer in their storytelling and give recommendations as to how an intention can be made more present by the light.

The next step, moving a work to the stage from the studio, creates a significant difference in how the ballet looks, and it is here that Jennifer works her magic. With the addition of costumes or sets, from the most detailed to the barest, light is the medium through which these elements come together to form a performance.

On stage, light could be its own character, especially in dance, where choreography and light infuse to sculpt and define the movement. The three-dimensional elements of this relationship are the key to perception of breadth and volume, but it must not be obtrusive. As Jennifer explains:

“The lighting designer has to be very careful not to be bigger than the dance.”

It was always her hope that the audience didn’t take too much notice of the light on stage. If one did take note, it could have been for all the wrong reasons (a stage shrouded in an excess of shadow can certainly be a performance-killer). It is the lighting designer’s job to use the light to not just make the dance visible, but to tell a story—one that is fitting and freeing, allowing an understanding and interpretation of the narrative.

Jennifer’s time as a lighting designer was sometimes difficult. It wasn’t a very glamorous job, and she often missed out on the recognition that the dancers, choreographers, costume designers and composers received. She frequently found herself traveling alone, having to fend for herself, needing to be strong. One must weather the bumps and bruises, she told me, to develop a shell, but also needs to stay sensitive to the surrounding world.

Jennifer made it through with her guiding force, “I’ve been just so in love with light, that those other things don’t matter.”

We should all hope to find something in our lives to talk about with as much reverence and passion as Jennifer does about light.

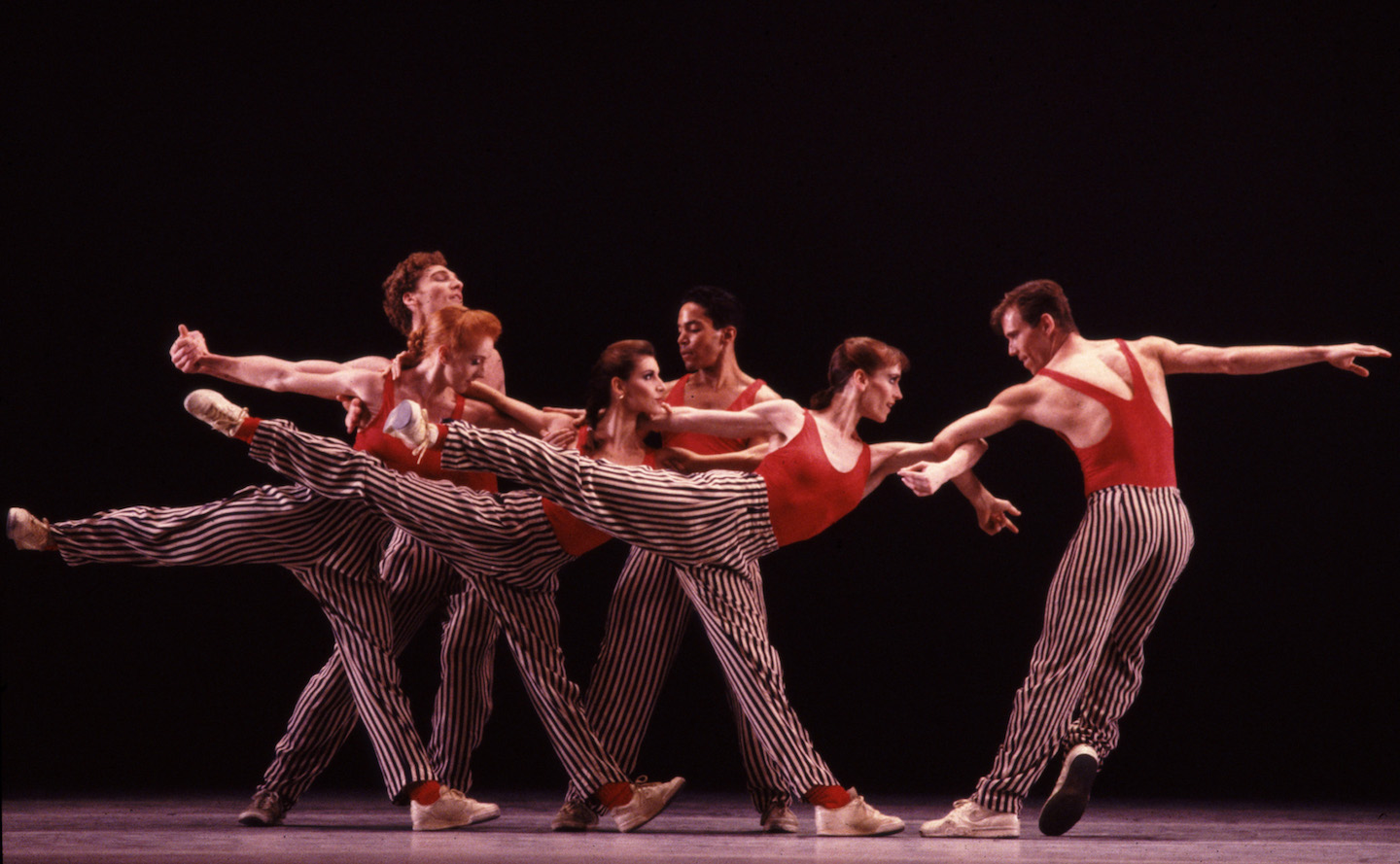

During the Fall 2019 season at the David H. Koch Theater, ABT presented Tharp Trio, a program of three Twyla Tharp ballets: The Brahms-Haydn Variations, Deuce Coupe and In the Upper Room. It was not just an evening of Twyla, but an evening of Jennifer Tipton too.

She had worked with the famed choreographer on all three ballets that spanned three decades. Having them shown together in one evening was a proud and significant moment for Jennifer, a celebration of many years of work.

The lighting featured in In the Upper Room is particularly striking. The beautiful interference of beaming white lights against semi-transparent fog on stage functions as a curtain through which the dancers can appear and disappear. They do not simply exit the stage, they are engulfed and released, their lingering energy fueling the progression of the dance.

Much has changed in lighting design over the years with new and evolving technology. Computer controls make some things possible that could not have been achieved before, such as the rhythm and dynamics in light transitions. There is an increased fluidity of the light that can be altered and manipulated more so than ever before.

Lights and color filters themselves have changed, and the use of LED lights is getting better, but Jennifer does have one gripe about this: “LEDs are not full spectrum lights, so I really don’t like LED light on skin very much. There are all colors in skin, so it needs a full spectrum—skin of all colors needs full spectrum light to not be flattened out.”

Technology has not threatened the organic creativity of before, for these are just new tools. The most important instruments come from within: “One still needs an eye. One still needs the mind to organize the light. The brain will find a way to organize what it’s seeing, whether you organize it or not.”

In this way, light can be the scenery, the highlighter, the focus, the innocuous presence on stage, but Jennifer hopes that, above all else, lighting designers will always continue to make it about the performer. For what is an empty stage with a set and lighting if there is no one to dance within it?

The writer, Bethany Beacham, joined ABT as Marketing Coordinator in 2020.