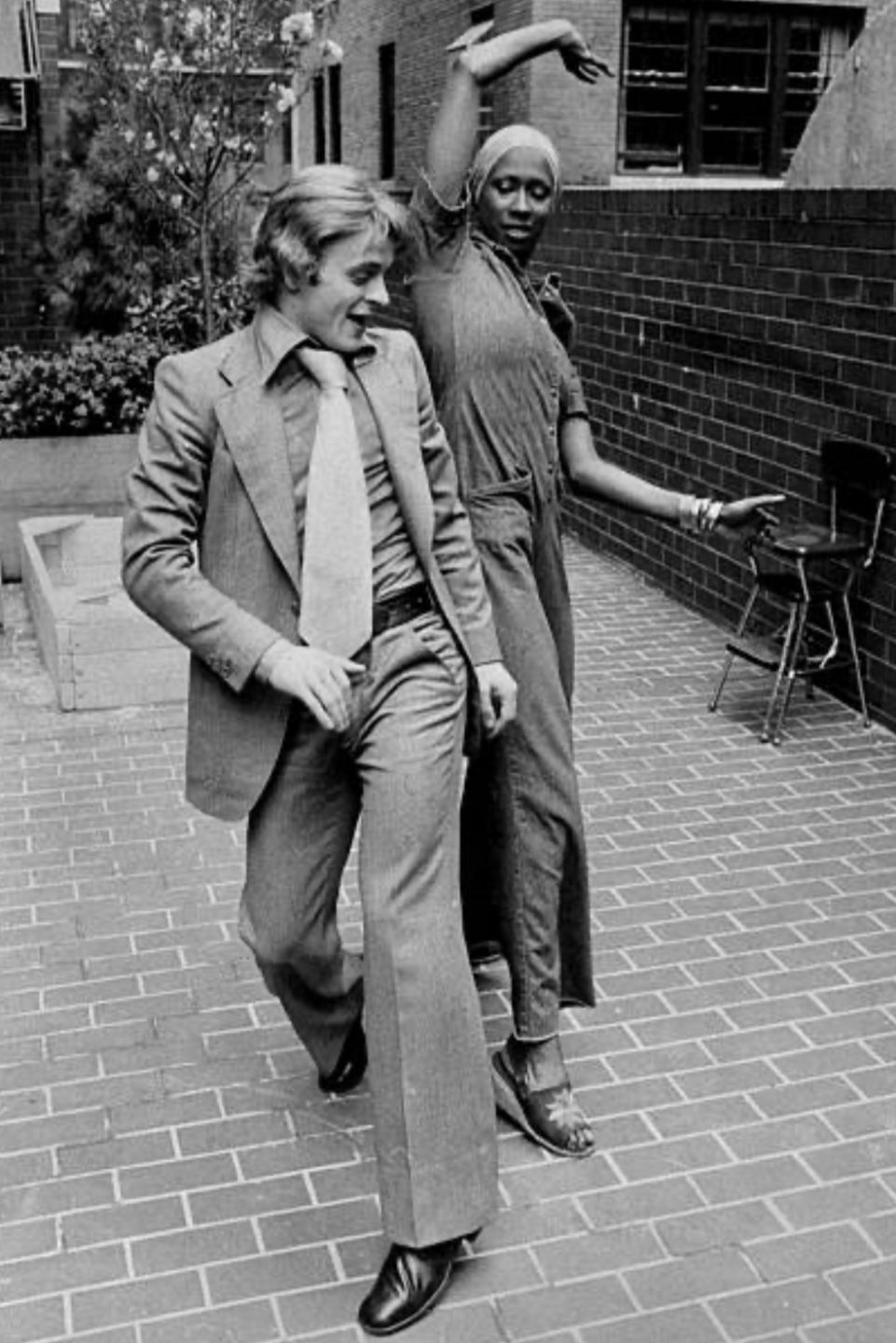

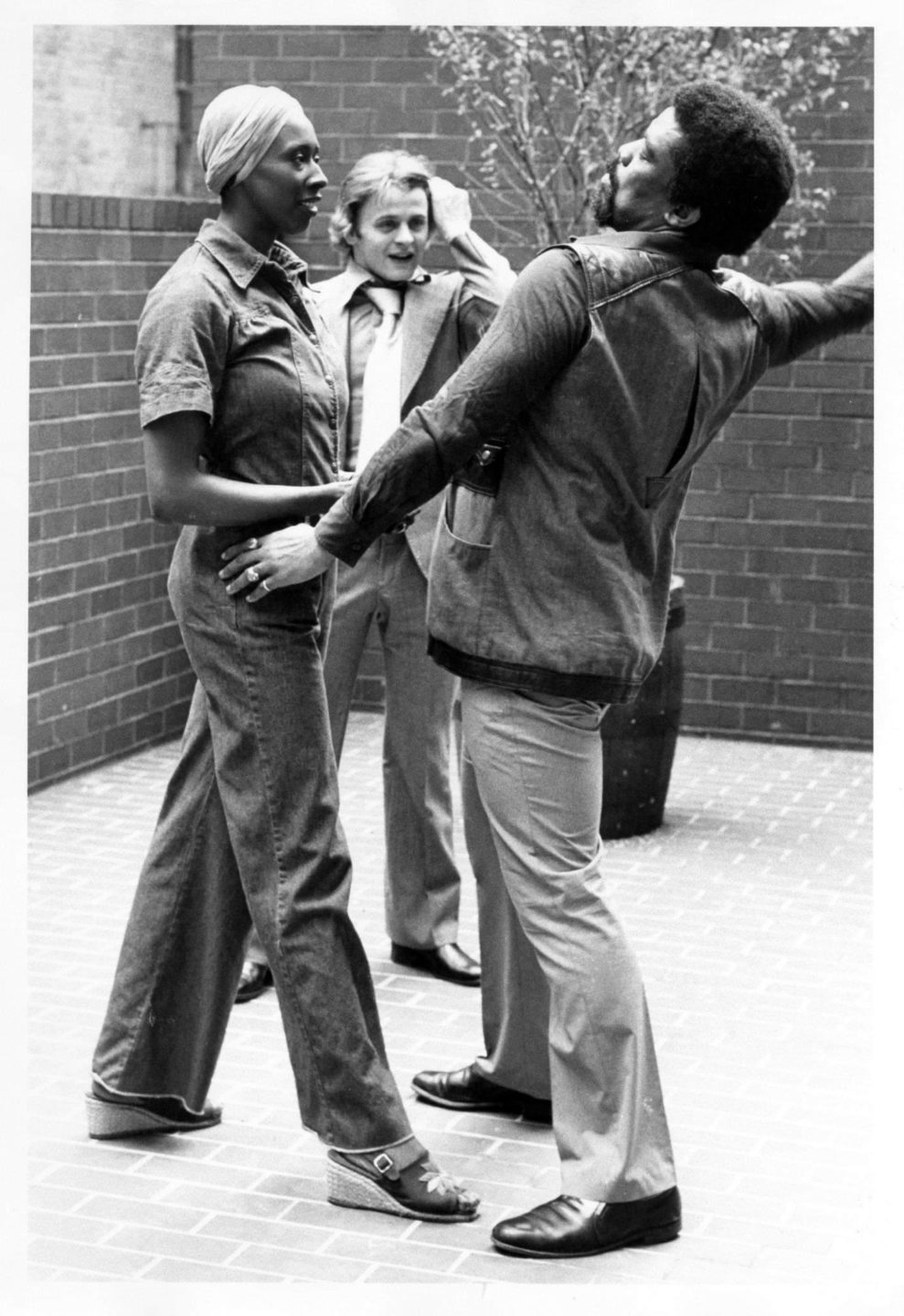

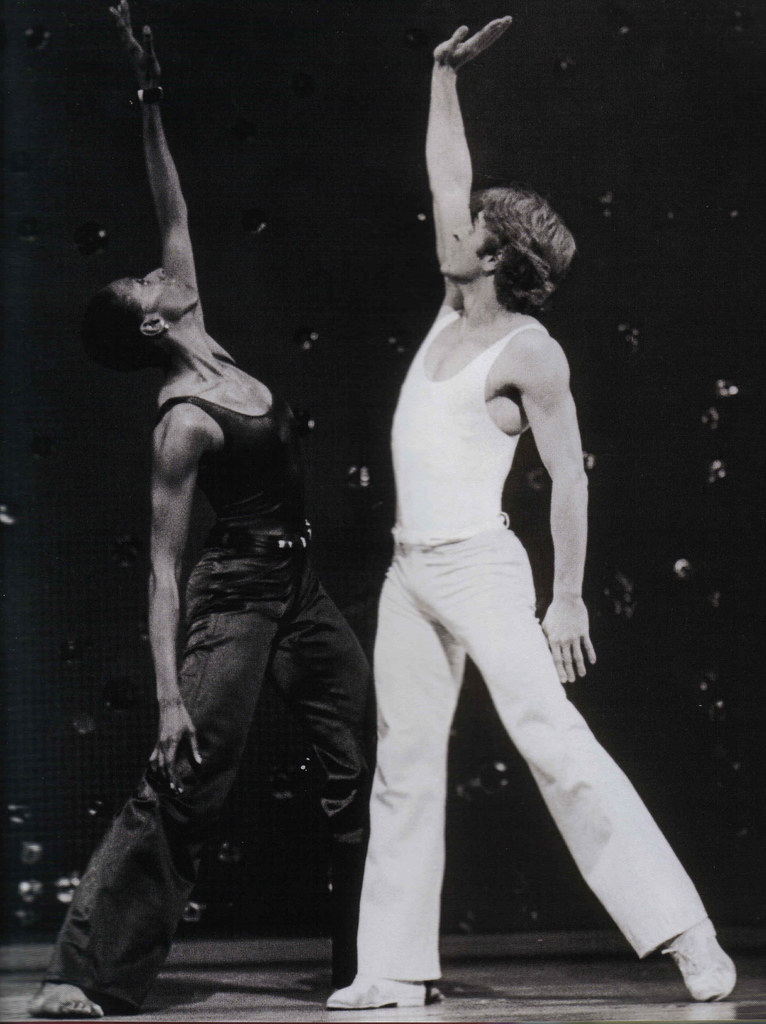

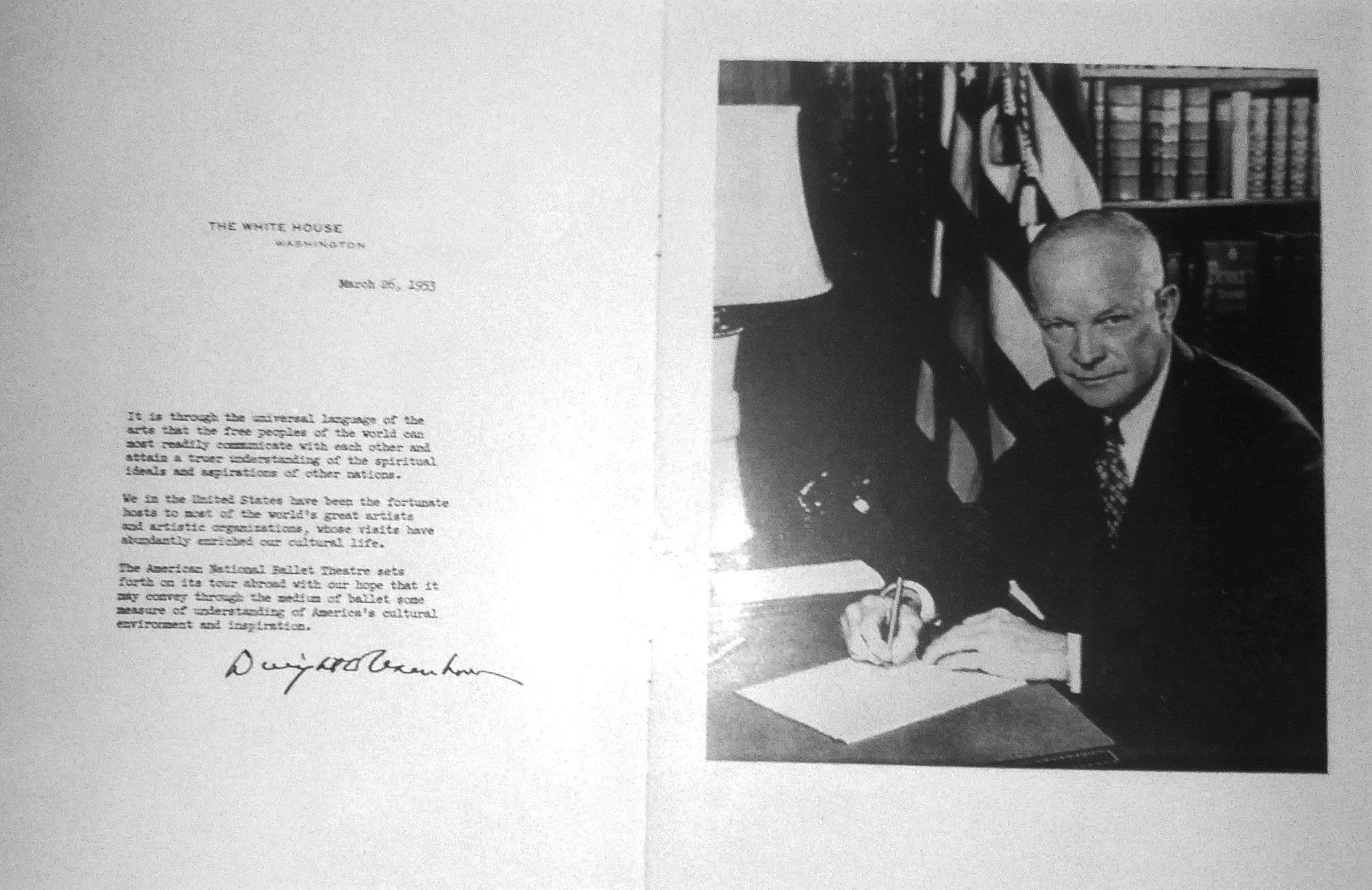

Lawaune Kennard and an unnamed dancer in Agnes de Mille’s Black Ritual, 1940. Photo: Carl Van Vechten.

Lawaune Kennard and an unnamed dancer in Agnes de Mille’s Black Ritual, 1940. Photo: Carl Van Vechten.Posted In

A Look Back at 80 YearsBlack History MonthFebruary 28, 2021

"My hope is that ABT will try to rebuild the oppressive structures of those that came before us into something new, something better."

The Beginning: The Negro Unit of Ballet Theatre and Agnes de Mille’s Black Ritual

Last year, more so than ever before, ballet’s hard shell around its humanness cracked and revealed the other side to its elusive beauty. Whimsy became relatable, excellence became humble, and one-by-one, our performances were dismantled by a global pandemic. Most importantly, ballet had a wake-up call. Racial injustice hit a national breaking point and became something we could no longer ignore as people or as an art form.

We are coming to the end of Black History Month where we have celebrated and highlighted the Company’s beautiful, powerful Black artists of the past, present, and future. ABT is making strides internally to foster an environment of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The organization is identifying changes that need to be made and is actively committing to eradicating the long-standing racial oppression that has always permeated classical ballet.

However, we cannot look forward without looking at our past, and I was asked to delve deeper into ABT’s = history. Remembering, seeking answers: this is how we make sense of who we are and inform who we want to be. I realized that I was entering into a negotiation with ABT’s past—recognizing achievements and triumphs, whilst acknowledging what went wrong.

So, I went back to the very beginning, to the infancy of Ballet Theatre, to understand how the organization played a part in perpetuating the marginalization and oppression of Black artists. I sought the untold stories of our failures – not to foster shame, not to damage ABT, but because it was the very least I could do.

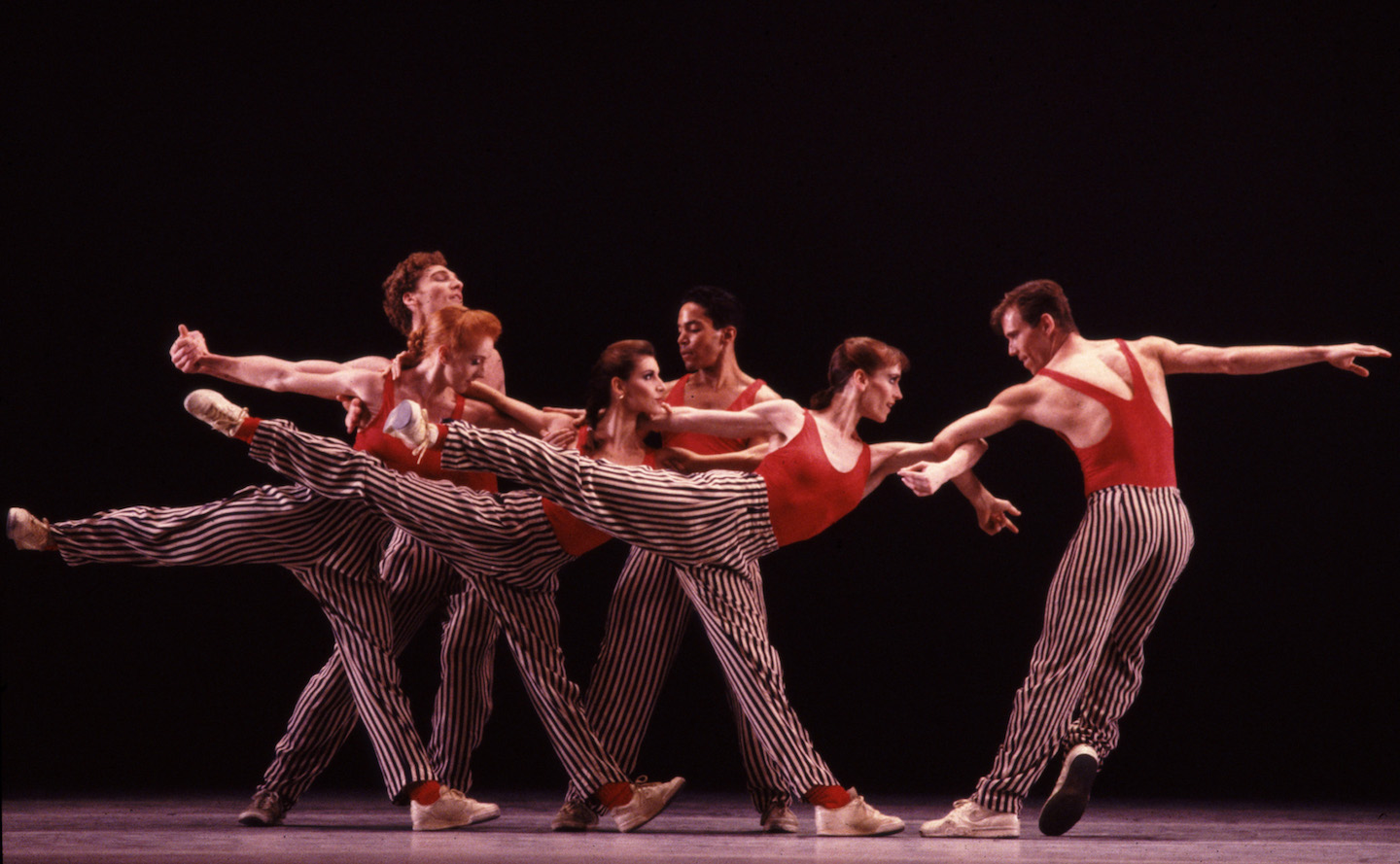

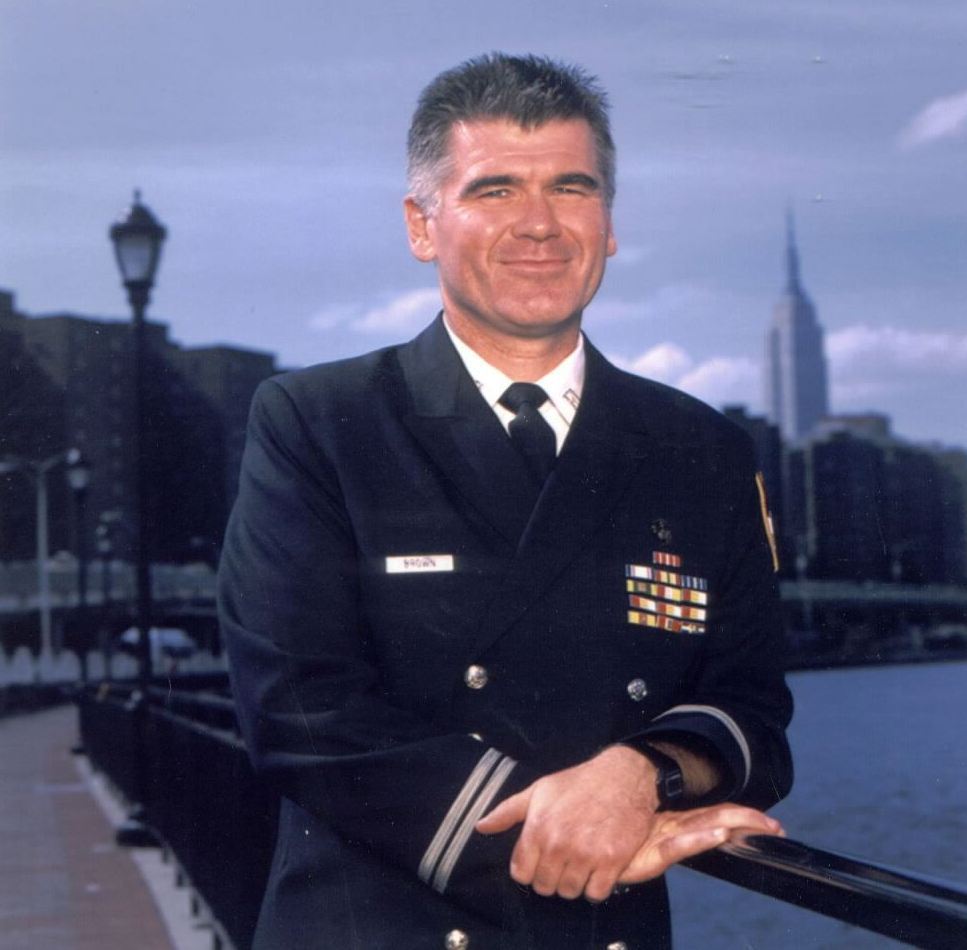

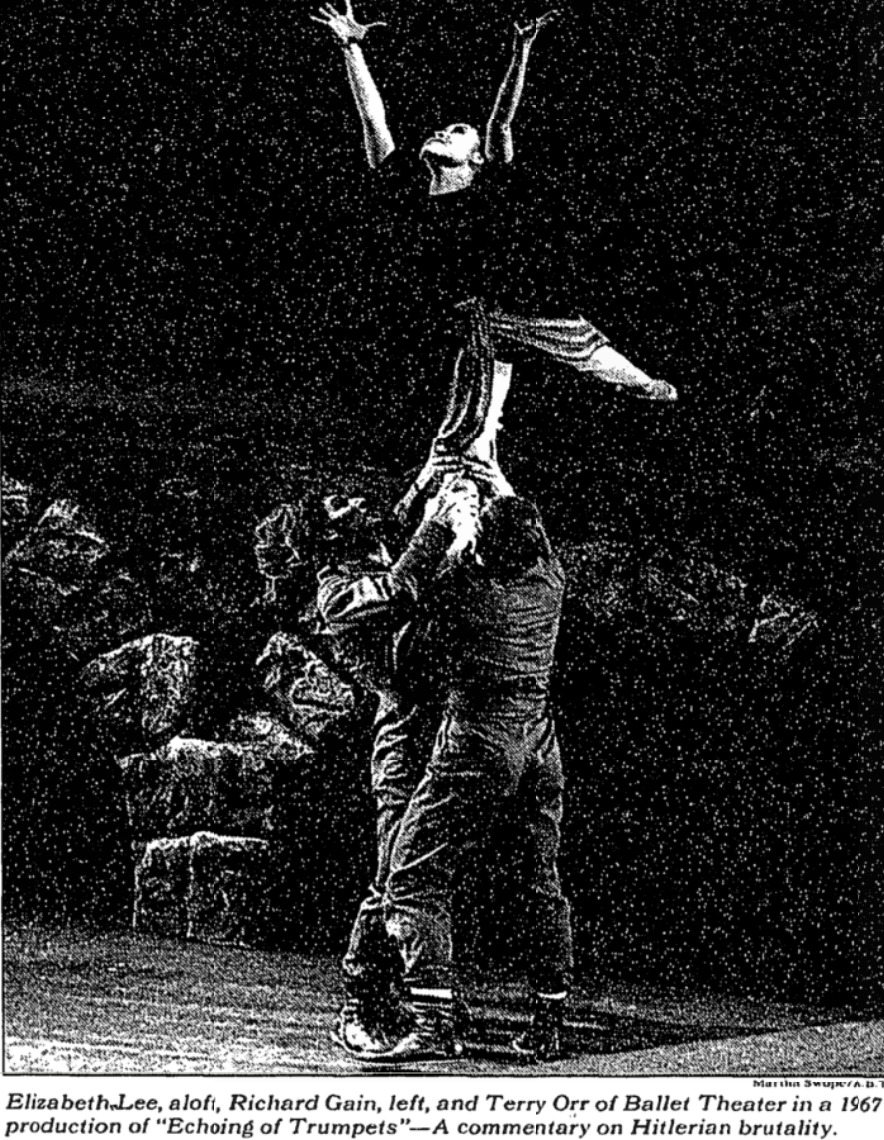

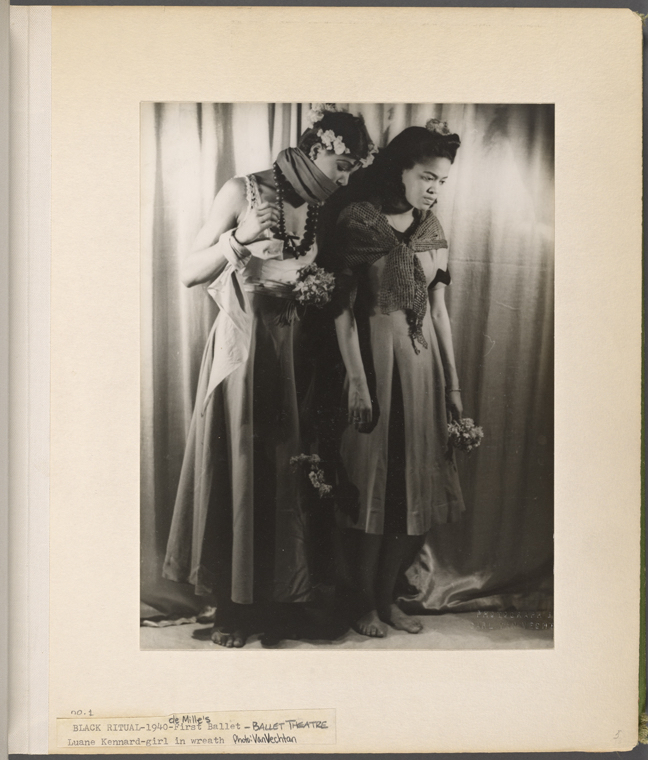

Lawaune Kennard, Lavinia Williams, Ann Jones, Dorothy Williams, Elizabeth Thompson, Evelyn Pilcher, Edith Ross, Valerie Black, Leonore Cox, Edith Hurd, Mabel Hart, Moudelle Bass, Clementine Collinwood, Carroll Ash, Bernice Willis, and Muriel Cook.

These are the names of the sixteen Black female dancers who starred in the Ballet Theatre Negro Unit’s only ballet, Black Ritual (Obeah). If you have never heard of the Ballet Theatre Negro Unit, you are not alone.

On the tail end of the Great Depression and the precipice of World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), a component of his New Deal to subsidize the creation of live art across the United States. Its purpose was not necessarily an attempt to save the suffering arts, but to provide economic relief and jobs to artists and theatre workers. The result produced The Negro Theatre Project, also known as a series of Negro Units, in 32 cities across the United States, including New York City, at a blossoming new company called Ballet Theatre.

At the inception of the company, Agnes de Mille was recruited by Richard Pleasant to choreograph for Ballet Theatre, but only under the condition that she could not perform in any of her ballets. De Mille agreed to climb on board, but she was not happy with the constraint. This inspired what would become the only ballet produced under the Negro Unit of Ballet Theatre: “Since I was not permitted to perform myself, I avoided comedy altogether in an impulse of stubborn negation and sought to do something as uncharacteristic and surprising as possible—an exotic work for Negroes.”

The ballet, Black Ritual, was choreographed on 16 new Black dancers who had professional and educational experience in dance, despite later claims that they were “unschooled” and “untrained.” De Mille’s frustration that she could not perform in her own ballet turned a choreographic project into something slightly more sinister in her objectification of the dancers and the ominous plot of the ballet, creating a division that formed the “other.”

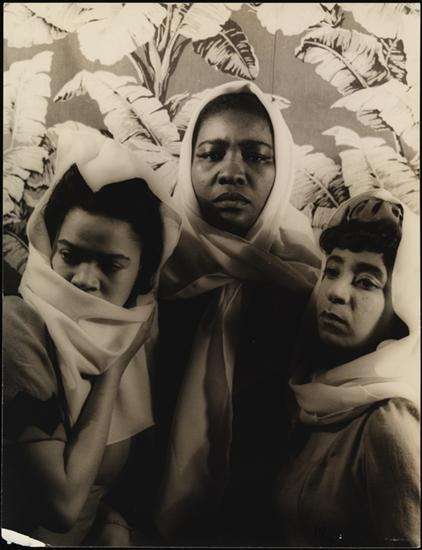

The plot of Black Ritual was centered around a group of “primitive” women who had congregated to put to death one of the women amongst them, who would carry their collective sorrows and troubles to Hell. In the ballet, they dance to the hills where they have their private ceremony. There the sacrificial girl dances herself into a frenzy in the midst of her executioners, who finally take her down before they rush back into their dark and mysterious forest.

The ballet’s subtitle (Obeah) refers to a type of Afro-Caribbean religious practice, but in presenting the ballet to the public, the company did not go further into specific cultural detail. The evening’s program, which did not name any of the Negro Unit’s dancers, read:

“Every primitive religion contains the ritual of blood sacrifice, such as the killing of the god, or the sanctified victim in proxy for the god. This annual destruction and rebirth compasses the regeneration of Man and Earth…This ritual scene makes no claim to authenticity. Set vaguely somewhere in the West Indies, it attempts only to project the psychological atmosphere of a primitive community during the performance of austere and vital ceremonies.”

Usually, and most evident in this case, the word “primitive” is not assumed to indicate a distance in time between the performance and the audience. The concept is not considered to mean “ancient” or “original”. In this context it defines the cultural “other” through the audience’s understanding that what they were meant to see was something barbaric and crude.

First performed one week into Ballet Theatre’s inaugural season on January 22, 1940, it was the first time Black dancers had appeared in a large-scale production from what was a typically all-white ballet company. Though some may have seen that as a bold move for a new, very different kind of ballet company, it did not stray from what Ballet Theatre was all about. In a letter to the World-Telegram of New York, publicists for Ballet Theatre singled out Black Ritual as an example of Ballet Theatre’s emerging identity: “This is a far cry from some of the traditional ballets being presented in the Ballet Theatre repertoire. But this was how the Ballet Theatre was meant to be—a combination of tradition and ultra-modernity.”

Unsurprisingly, the ballet was received with a wide variety of reviews. Black critics felt it was a meaningful accomplishment, but white critics were more inclined to see it as a novel anomaly in the ballet world, viewing it through the marginalizing lens that classical ballet was not appropriate for “the Negro.” Nevertheless, first-hand accounts, such as one featured in the Chicago Defender, spoke of a triumphant evening:

“When the Ballet Theatre opened its doors for the first time at Rockefeller Center last Monday evening, little did it realize its occupants would behold one of the greatest performances in the history of the ballet—little did it realize that they would really know what it meant to be spell-bound—little did it realize the curtains of its theatre would rise and fall once, twice, ten or even more times, amid shouts of “bravo” and deafening sounds of handclaps while a group of Race girls stood to receive the applause – but that is just what happened.”

Black Ritual was performed only three times over the course of the season, and when the curtain closed on Ballet Theatre’s three-week run at Radio City, the Negro Unit was disbanded. Some say that the Unit lacked a singular artistic vision that would carry it forward. Others say it was to save money.

True, a ballet company in its infancy would always face financial struggles as it wobbled onto its feet, but the dancers in the Negro Unit were paid only a fraction of what their white corps de ballet counterparts were paid—a mere $10 to the latter’s $40. The only certainty of the Negro Unit’s disbandment, however, is that it has disappeared into the forgotten corners of the company’s history with a glaring truth: there was a limit to how progressive and inclusive the company was willing to be.

A confidential, unsigned letter at Ballet Theatre from October 1940 revealed evidence that there were plans to redo Black Ritual with an all-white cast. Although the correspondence petered out six months later with nothing coming to fruition, the messages passed back and forth showed no sign of concern about this casting switch. De Mille was adamant that the ballet should remain in the company’s repertory despite the injudicious changes that would dismantle the ballet’s core.

Along with the rest of the world, each and every one of us shoulder the responsibility of the past—the responsibility to not just recognize and verbalize our history, but the responsibility to do something with the knowledge we gain through self-examination. While learning this story, I sought honesty. I sought the mistakes Ballet Theatre made many years ago. My hope is that ABT will try to rebuild the oppressive structures of those that came before us into something new, something better.

I could never give these dancers and their story the level of justice they deserve. I learned how Ballet Theatre failed the talented, valuable dancers in the Negro Unit. From being left out of the performance’s program to being grossly underpaid, to disbarring the Negro Unit and not giving any of the dancers company contracts, Ballet Theatre failed. It should not have been that way. I can only give these women today, this moment in history, a space to be heard, to be seen, and to be celebrated, but there is more to be done. There is more space to be given, more voices to amplify, more reckoning to grapple with.

We must all remember that change is not finite. It is a journey, a process. Black History Month may only be a small portion of the year, but this is just the beginning.

The writer, Bethany Beacham, joined ABT as Marketing Coordinator in January 2020.