March 26, 2021

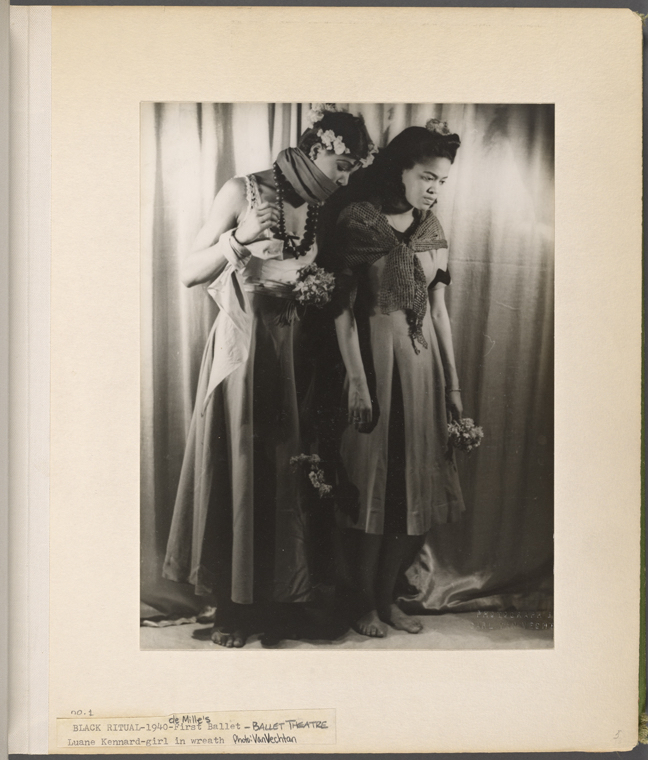

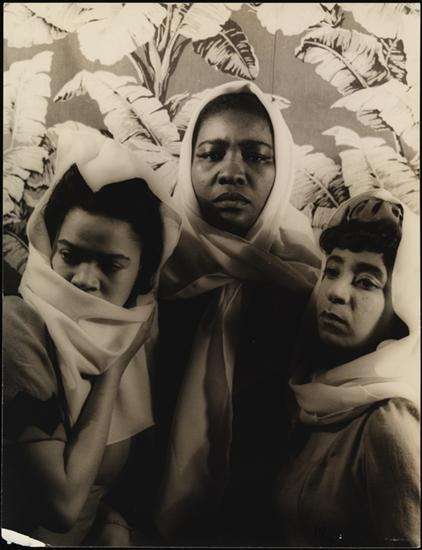

For Women's History Month, SideBarre is highlighting the extraordinary women who have helped to shape ABT through the years.

"It's how we speak to one another and how we respect one another. It’s about how we can all sit down at the table and at least be able to be heard. I think that's the most important thing for all of us.”

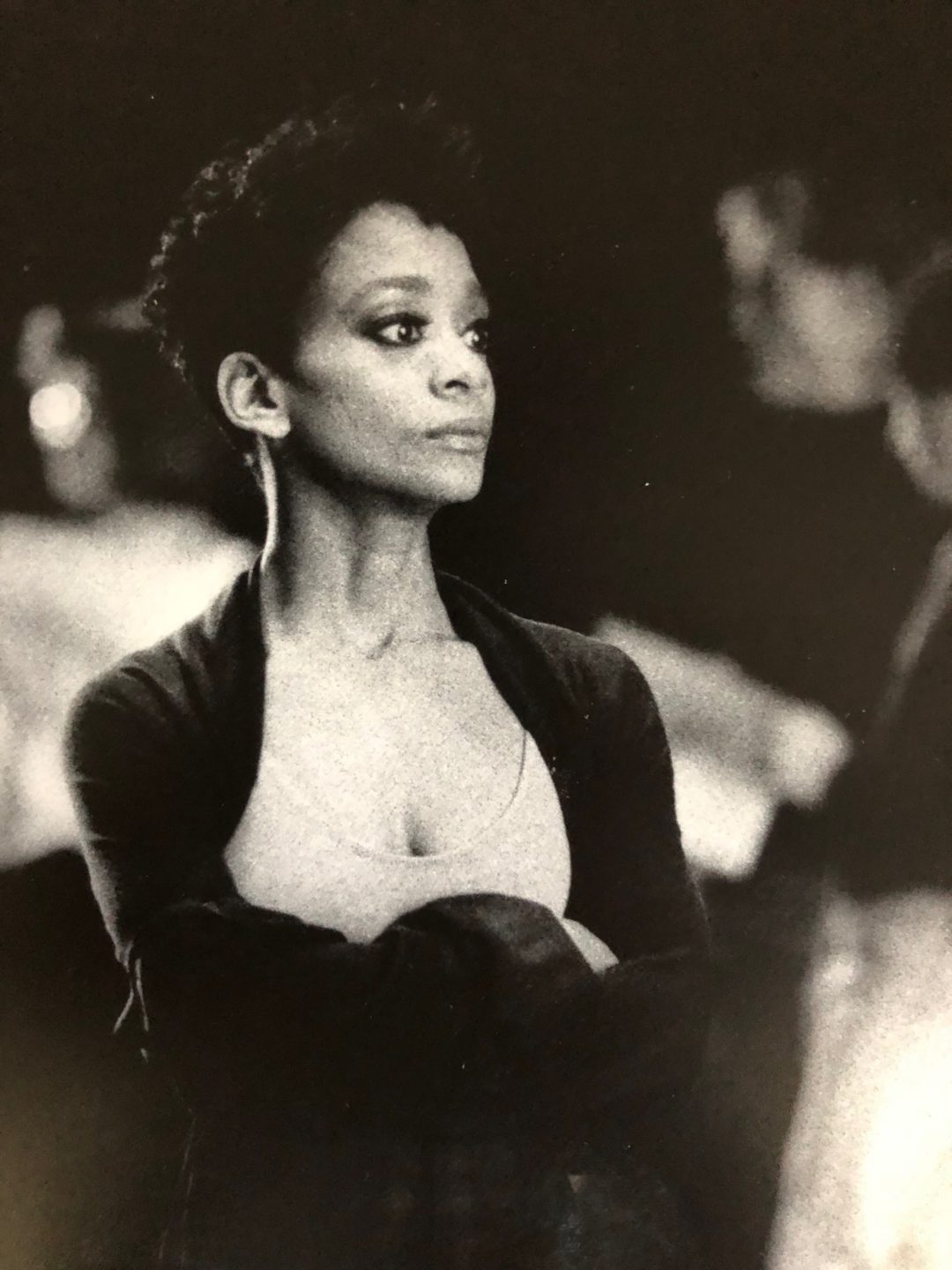

Even contained in a little rectangle on Zoom, Shelley Washington’s vivaciousness and elegance demand attention. Her huge, soulful eyes are mesmerizing, her presence generous. For almost two hours, I had the privilege of interviewing Shelley about her life and her time at American Ballet Theatre.

Shelley was the second Black female Soloist that ABT had ever had, a position she held from 1988-1990. The path to such a coveted position in a ballet company is typically straightforward. Young dancers, with years of training under their belts, fight for coveted apprenticeships. From there, they pay their dues in the corps de ballet and after many more years of hard work, a select few are chosen to become soloists or principal dancers. This was not the case for Shelley. Instead, she took her own uniquely beautiful path.

From a young age, it was obvious that Shelley had a natural gift for dance and performance, and after years of training, with the help of her mother and her teacher, Shelley found herself at Interlochen Arts Academy. At age 14, for the first time, Shelley was with people who were like her, and indeed there is a unique kind of magic that happens when you find your people. You begin to understand yourself in a different way, in the context of a group, not just as an individual.

“Interestingly,” Shelley said of finding this community she so easily fit into, “it wasn’t that they were Black. It was that they all were dancers, artists, musicians, actors. They were me. They were the people that were seeking something different from the curriculum of their high school. They were me because they had parents or mentors who sent them to the school. All of those students looked like me.”

Coming from a small town in Michigan, where Shelley’s family was the first and only Black family, this newfound space allowed her to blossom.

Following her high school years, Shelley moved to New York to attend Juilliard. From there, it took no time for Shelley’s professional career to come to fruition. At the end of her two years at Juilliard, Shelley was asked to audition for the Martha Graham Company. What followed was a whirlwind year of international touring with Martha, who collaborated with great artists such as Halston and Andy Warhol and hosted internationally renowned ballet stars Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. It ended in true fashion, with a gondola ride to Martha’s hotel room in Venice. Shelley had been offered a position in Twyla Tharp Dance, so she traveled the canals to tell Martha. Somebody who had seen Shelley take class in 1973 at American University with Twyla remembered her and asked her to audition. Twyla swiftly asked Shelley to join her ranks.

We now fast forward to 1988. Twyla Tharp was invited by Mikhail Baryshnikov, then Artistic Director of ABT, to begin working with the Company, and in that transition, Twyla brought four of her dancers with her – Shelley among them. Because of her position with Twyla and the amount of money she made, which was more than a corps de ballet member, Shelley became a Soloist. For the ABT dancers who were on the traditional path, this was not received well.

“Now you can imagine, I’m 34 years old, I’m a Soloist at Ballet Theatre, I’m not a classical ballet dancer, and I’m Black. Think about how incredible Misha was to do that and Twyla to have me in there,” Shelley recalls.

The transition was not easy for Shelley, and even Twyla felt that she had let her down, as she later wrote in her book, Push Comes to Shove. Shelley, whom Twyla referred to in her book as one of her “power women,” was at the pinnacle of her career and had been with Twyla for 13 years. As one of the senior dancers in Tharp’s company, Shelley had to rapidly change the course of her career. Even Twyla herself said that Shelley was the only one without pointe shoes in the locker room.

Shelley remembers her first class with ABT as particularly challenging, “I had to walk into a class with all those dancers, and you can imagine what they were all thinking. I can imagine what they were mostly thinking, you know, How is this happening? and How can she be a Soloist? and I’ve been here for all these years. We were in California. I can’t remember who was teaching, maybe Jurgen Schneider, and I went to one barre and as I was standing there, Misha came over and stood next to me. He left his barre and came and stood next to me, as if to say, Okay, we’re in this together. Let’s do this. I’ve got your back.”

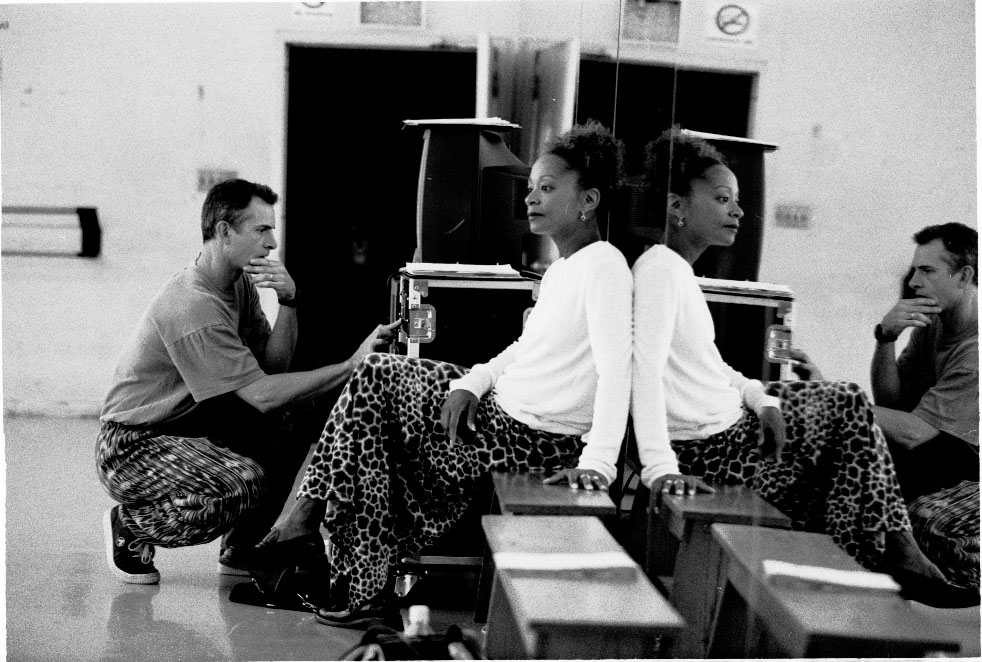

The first thing Shelley did at ABT was stage In the Upper Room, a ballet that had been choreographed on her and held a special place in her heart. As one of Twyla’s most experienced company members, Shelley not only came to ABT as a dancer and performed in many of the Company’s works, but also as a regisseur.

Though she was taking on new responsibility and entering into a whole other phase of her career, it was, nevertheless, a huge loss of what she left behind. She didn’t dance as she did before. “I decided that I really couldn’t dance Upper Room because I was so used to dancing every piece every night, seven shows a week, and I couldn’t bear the thought of doing it once every week or so. It was just too much.”

At this point in our interview, Shelley paused and thought for a moment, before taking me back to 1969, “I never told my mother. I never told anyone at the school. I never told my sister. I remember my teacher taking me aside and saying, You know, you have beautiful feet and legs and arms and you’re a beautiful dancer. I really think you should be a modern dancer or go into movies or Broadway, because you’ll never be a ballet dancer because of the color of your skin. And if you got into a company, you would be the gypsy. But I never stopped taking ballet class. I just thought, Okay, well, I don’t want to be a gypsy in a ballet company. I’ll show you.”

And show him, she did. She came full circle, ending her career after a few years at ABT with one of the biggest roles she had ever performed: Madge in La Sylphide. Fondly remembering her final curtain call at the Met, she said wistfully, “It was pretty wonderful.”

Shelley didn’t stay a Soloist for very long. It wasn’t something she had strived for her whole life. She had already had a prolific career with Twyla. She understood that there could be only so many Soloists at ABT and that there was a corps de ballet full of beautiful dancers who had been working to move up the ranks their whole lives. She decided to retire and became a full-time regisseur.

“You know, I love dance. I love ballet. I loved my time there, but it was not easy. It was not easy in the beginning, but then for me, nothing really ever has been.”

Shelley was so used to changing schools in the middle of the school year from such a young age because her father’s job was constantly moving. She was so used to being the only one who looked a certain way, whether in junior high in Michigan or in Germany.

Coming to ABT, Shelley said, was the same thing. And throughout these experiences, she kept returning to the wisdom of her grandmother—do your work, keep your focus, be a good girl, be honest, and it will work. Above all, Shelley’s grandmother told her she believed in her, and it is evident that she carries those words and the faith, strength, love, and support from her family with her today.

Shelley respected the dancers at ABT greatly, but they also respected her—her work ethic, her insight, and her determination. A true pioneer, she respects her own bravery in coming to ABT, and the bravery of others to welcome the Tharp dancers when it could have been so easy to reject them.

I want to end this interview with Shelley’s own words. In our few hours together, I had already learned so much from Shelley. I was awestruck of the strength and grace in her words and in her heart. With so much change in the world, so much that has come to the surface, I was curious to hear what she thought the future might hold for the ballet world:

“I don’t know what the future is. I know that it can only get better because we are talking, we are dealing, we are listening. We are listening. So perhaps that’s the biggest thing—maybe we’ve always talked, but no one has listened. We can’t go back and fix things from the past, but we can acknowledge them and know that they’re true and that hurt and pain and suffering are there. It’s there and now maybe we can move past that.”

“That teacher could have said, You’ll never be a ballet dancer because of the structure of your hips, as opposed to, because of the color of your skin, but if I’m going to stay positive, I was a Soloist at ABT. I can say I proved you wrong, as opposed to, I’m going to get that person in trouble. Even at 14, I knew it was heavy. I think the first time I ever talked about it was last year.

“Then you start hearing other dancers’ stories, and you’re just like, whoa. I think it was easy to live in our own little bubbles and now they’ve been broken. So, perhaps it’s not only listening. It’s how we speak to one another and how we respect one another. It’s about how we can all sit down at the table and at least be able to be heard. I think that’s the most important thing for all of us.”

Shelley Washington, I hear you. Thank you for allowing me to listen.

The writer, Bethany Beacham, joined ABT as Marketing Coordinator in January 2020.